Classical science

one of the earliest works in greek astronomy to survive in its entirety

Autolyci De vario ortu et occasu astrorum inerrantium libri dvo nunc primum de graeca lingua in latinam conuersi … de Vaticana Bibliotheca deprompti. Josepho Avria, neapolitano, interprete. Rome, Vincenzo Accolti, 1588.

£7500

Editio princeps, very rare, of Autolycus' work On the Rising and Setting of the Fixed Stars, and one of several Greek scientific classics including Euclid's Elements that first appeared in Latin translation well before their first printings in the original Greek.

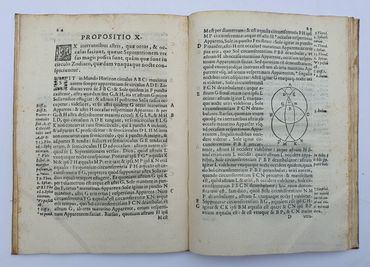

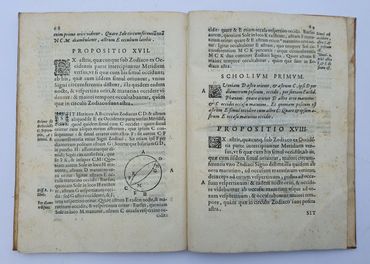

On Risings and Settings is strictly astronomical and consists of two complementary treatises or “books.” True and apparent morning and evening risings and settings of stars are distinguished. Autolycus assumes that the celestial sphere completes one revolution during a day and a night; that the sun moves in a direction opposite to the diurnal rotation and traverses the ecliptic in one year; that by day the stars are not visible above the horizon owing to the light of the sun; and that a star above the horizon is visible only if the sun is 15° or more below the horizon measured along the zodiac (i.e., half a zodiacal sign or more).

‘The theorems are closely interrelated. Autolycus explains, for example, that the rising of a star is visible only between the visible morning rising and the visible evening rising, a period of less than half a year; similarly, he shows that the setting of a star is visible only in the interval from the visible morning setting to the visible evening setting, again a period of less than half a year. Another theorem states that the time from visible morning rising to visible morning setting is more than, equal to, or less than half a year if the star is north of, on, or south of the ecliptic, respectively’ (DSB).

The Elements in english

[EUCLID]. DECHASLES, Claude-François Milliet. The Elements of Euclid explain’d in a new but most easie method ... Oxford, Lichfield for Anthony Stephens, 1685.

£2250

A very attractive copy in a contemporary English binding of the first edition of this English translation of Dechasles’s Euclidis Elementorum libri octo, a paraphrase of Euclid’s Elements.

This work covers Books 1 to 6, together with Books 11 and 12, of Euclid’s Elements. Another English edition was published in London by M Gillyflower and W Freeman in the same year, the translation being by Reeve Williams.

‘Dechales [is also known to have] adopted Galileo’s theory of motion, where he introduced several original views and developments.

not just ‘meteors’

RAO, Cesare. I Meteori. I quali contengono quanto intorno a tal materia si puo desiderare. Ridotti a tanta agevolezza, che da qual si voglia, ogni poco ne gli studi essercitato, potranno facilmente e con prestezza esser intesi … Venice, Giovanni Varisco, 1582.

£1600

First edition of Cesare Rao’s complete course of natural philosophy.

Rao discusses the celestial spheres, atmospheric phenomena and their causes, rivers, the seas, the winds, earthquakes and storms, the rainbow, and so forth. One chapter discusses comets as portents of trouble.

‘With I Meteori Rao eclectically intertwines heterogeneous ‘opinions’ bound to both classic and medieval tradition as well as to that of the Renaissance - Theophrastus, Ptolemy, Alexander of Aphrodisias, Averroes, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Giovanni Pontano, Giovan Camillo Maffei - demonstrating his vast competence in the fields of astrology and natural science’ (translated from Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani).

A SERIOUS DEPARTURE FROM ARISTOTLE’S PHYSICS?

THEOPHRASTUS. Περι πυρος [with:] De igne. Paris, Adrien Turnèbe, 1552[-1553].

£5500

First edition of Turnèbe’s annotated Latin translation of Theophrastus’ interesting work on Fire, a work sometimes interpreted as a serious departure from Aristotle’s physics, and here bound with Turnèbe’s printing of the original Greek text, which is rarely present.

‘Concerning Theophrastus’ account of the four elements, it has been debated to what extent this conforms to the Aristotelian doctrine. In particular, it is not clear whether Theophrastus followed Aristotle in holding that the heavens are made of a fifth element, the ether, distinct from the four sublunary elements, or whether he claimed that the heavens are simply made of fire …

It has been argued, for instance, that Theophrastus abandoned the fifth element, but used it only in arguments against Plato without endorsing it himself (see Steinmetz 1964). There is no doubt, on the other hand, that he gave prominence to the element of fire' (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, online).