Philosophy, logic, and law

ernst mach's copy of ‘the right to live and the duty to die’ - humanitarianism and common sense from the pen of a genius

POPPER, Josef. Das Recht zu leben und die Pflicht zu sterben. Socialphilosophische Betrachtungen, anknüpfend an die Bedeutung Voltaire’s für die neuere Zeit. Zu seinem 100. Todestage (30. Mai. 1878). Leipzig, Erich Koschny, 1878.

Sold

Presentation copy inscribed to his close friend, Ernst Mach, of the extremely rare first edition of this highly interesting and influential publication by Popper-Lynkeus, a man widely considered a genius.

‘As a scientist Popper was far ahead of his time. In 1862 he proposed a system for the electrical transmission of energy, but sent the monograph to the Vienna Academy of Sciences in a sealed letter to be opened 20 years later. He discussed the possible existence of quanta of energy before Max Planck enunciated the quantum theory; in 1884 he tried to relate matter and energy, 20 years before Einstein’s theory of relativity; and in 1888 discussed the possibility of lightweight steam engines for flying machines in a treatise, Flugtechnik (1889). In Phantasien eines Realisten (2 vols., 1899), suppressed by the Austrian government as “immoral,” he anticipated, as Freud himself acknowledged, the fundamental basis from which the latter elaborated his theory of dreams.

‘Popper was best known, however, for his writings on social reform. In his first work of this nature, Das Recht zu Leben und die Pflicht zu Sterben … (1878), he contrasted man’s natural right to live with the alleged obligation to sacrifice himself when required to do so by the state. He denied that man has a duty to let himself be killed when ordered and, in Die allgemeine Naehrpflicht als Loesung der sozialen Frage (1912), advocated the right of the individual to live in freedom and dignity within the framework of a social system created for the benefit of its members. Popper’s solution to social problems was the formation of a labor force (Naehrarmee) whose purpose was “producing or procuring all that physiology and hygiene show to be absolutely indispensable.” This was to be regarded as a minimum contribution by every member of society. Popper’s philosophy differed from Marxism, in that it was based on simple humanitarianism and common sense and endeavored to eliminate class hatred by a synthesis of socialism and realism. In trying to revive Voltaire’s philosophy, he advocated a policy which in fact became crystallized in the modern welfare state.

‘Popper regarded metaphysics, theology, and traditional religion as harmful, and to be eliminated from an economically and socially reformed state. He saw religion, especially Christianity, as opposed to genuine individual human values, and believed that education, especially about the history of religions, could lead to a superstition-free culture’ (Encyclopedia.com, online).

‘Among the admirers of Popper-Lynkeus were physicists Albert Einstein and Ernst Mach; philosophers Martin Buber and Hugo Bergmann, chemist Wilhelm Ostwald; mathematician Richard von Mises, statistician Karl Ballod (Kārlis Balodis); physiologist Theodor Baer; psychologist Sigmund Freud; writers Max Brod, Stefan Zweig, and Arthur Schnitzler; and the founder of the Zionist Revisionist movement, Ze’ev Jabotinsky’ (Wikipedia).

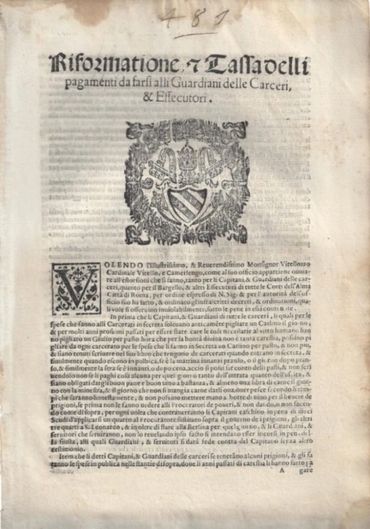

PRISON REGULATIONS AND PRISONERS’ RIGHTS IN 16TH-CENTURY ROME

[POPE PIUS V, Saint]. Reformatione, e tassa delli pagamenti da farsi alli guardiani delle carceri, et essecutori. [Rome, Blado, 1566].

£1750

A highly interesting and very rare papal decree in the vernacular on Roman prison regulations, addressing corruption and extortion prevalent among wardens and captains, and prisoners’ rights.

With law and its application greatly differing throughout Italian states and provinces at the time, this bull provides rare contemporary insight into corruption within the judicial system, specifically the extortion of secret payments through prison wardens and their superiors, and gives official guidelines to both wardens and prisoners.

the death of wittgenstein: eccentric or genius?

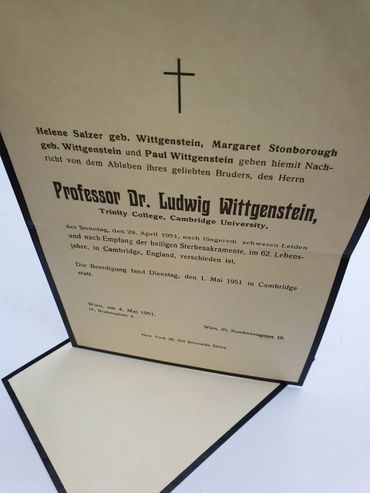

[WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig]. Original printed death notice. Vienna, May 4, 1951.

£8500

An exceptional memento: the announcement by Helene Salzer, born Wittgenstein, Margaret Stonborough, born Wittgentstein, and Paul Wittgenstein of their brother’s death in Cambridge, England, six days earlier, on April 29, 1951, and his burial on May 1.

Three of Ludwig’s four brothers – Hans, Rudi, and Kurt - committed suicide, which Wittgenstein had also contemplated; Hermine died in February 1950, a little over a year before her famous and youngest brother. Ludwig’s death is here jointly announced by all of his surviving siblings, Helene, Margaret, whose husband, Jerome Stonborough also had committed suicide 13 years earlier, and Paul. The note mentions Ludwig to have succumbed on Sunday, April 29, after prolonged grave illness, and after having received the last rites.

The latter note is of some interest regarding Wittgenstein’s faith and relationship with Christianity, which changed over time. Baptized and educated a Catholic, he lost his faith and became an atheist whilst attending the Realschule in Linz as a teenager in 1903-1906. It is also well documented though, that whilst resisting formal religion, he was always sincerely disposed towards religious faith, developing a deepening spirituality with age.

This death note was never posted; the original envelope remained unused and is in virgin state. It is thus likely that it remained in the possession of one of Wittgenstein’s siblings until it found its way into the open.